- Home

- Mike Mahan

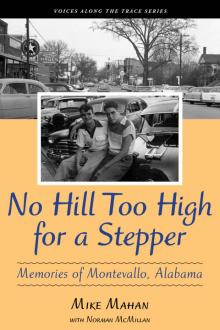

No Hill Too High for a Stepper Page 7

No Hill Too High for a Stepper Read online

Page 7

I should have taken my leave then, but something made me say, “Don’t you think that could be dangerous? A bird like that could bring some kind of disease into the house.”

Her face reddened, her eyes bulged, and she took in a menacing breath. She reached down and took a stick of stove wood from the box and hurled it at me with all her might. Luckily, I ducked and it missed me, but I decided not to wait around for another. I grabbed my notebook and my jacket and fled, hearing only two more words out of Adelaide’s mouth: “Smart aleck.”

I ran up the hill to a house occupied by Adelaide’s nephew, Edward. When I told him what Adelaide had done, he broke out laughing. “Well, you are not the first to have a stick of stove wood thrown at him. I thought you knew that was her weapon of choice.” In fact, I expect he preferred she use stove wood than her sharp tongue, because Edward had had plenty of opportunities to be assaulted. He told me that once when she was working outside he and a friend got Adelaide’s single-shot .22 rifle and wound up shooting a hole through the friend’s toe. Adelaide came running when she heard the gunfire, mad as one of her bees, and she threatened to whip them both, but settled for a severe tongue-lashing after viewing the wounded toe.

Adelaide was quite a character, but it was her older brother Jesse Jr. who most captured my boyhood fancy. From an early age I saw photographs of this massive man standing in the company of men, with a pistol in a leather holster strapped on his right hip and a machete in his hand. He wore a large hat, pants that fit tightly below the knee, and high, laced boots. He was without a doubt the central figure in the photo.

Perhaps inspired by his maternal Uncle Kevin Cunningham, Jesse had a strong case of wanderlust. Kevin was himself a world traveler. He was a collector, and when he died the family found menus he had collected at fine restaurants throughout Europe and in the states, as well as buttons and tokens from various places he had visited. I have his small card the size of a credit card from the late 1800s that lists all the places in New York City where one could make long-distance phone calls.

Kevin became an expert on diatom fossils and traded them with others across the country. I have many of his letters, which he printed in India ink in tiny, precise letters. I also have a map of his travels on horseback collecting diatoms in Mexico. It became clear to me that Kevin had plenty of stories that would have inspired both Adelaide and Jesse.

Kevin Cunningham, world traveler, adventurer, scientist, and scholar. He was the brother of Adelaide and Jesse Jr.’s mother, Anna.

Scribbled on the reverse of this photograph, “The start to Central America, Oulick, Mahan & Creary.” Jesse Jr., center, is equipped leaving Brierfield in the late 1890s for the island of Utila, Honduras.

In the late 1800s Jesse, then in his early twenties, left Brierfield with a friend for Honduras, where he expected to make his fortune. He had been told that the land there was almost free. I began to piece together his story listening to my aunts Maggie and Adelaide, both of whom lived in Honduras for a while, as well as to the tales Dad and others told me. I also learned that Dad’s older brother Cary went to Honduras after World War I and helped build a railroad for the United Fruit Company. In addition, the family had saved some letters from Jesse. So I knew a good bit about this distinctive kinsman.

Jesse first set up on the Isle of Utila, one of the bay islands that was settled by the English in the mid-1800s. A woman was among the first to come there, and she populated the island with offspring from two men. It is likely that Jesse was attracted to Utila because English-speaking people were there. An excellent carpenter, he quickly became a valuable member of the populace. On the island was a Methodist church that needed to be enlarged, and Jesse took on that job. The church had been perpendicular to the sea, but he decided to turn it to make it parallel, and he cut it in half and enlarged it in length and made other improvements. Jesse further established himself by marrying a sea captain’s daughter, but the marriage ended sadly when she died giving birth to a daughter, who also died. Subsequently, he married Rosa St. Martin, from a prominent family in La Ceiba, and they moved to the plantation headquarters near the small community of La Union. He began looking around for a plantation site and found one north of La Union, in the flatlands before the mountains began to rise up. He not only grew bananas, but he also built a railroad to take bananas to the port for shipping and established a commissary at the port site.

Jesse W. Mahan Jr., seated middle row, third from right, with banana plantation workers. Note the surveying instruments, machetes, and guns.

Both Adelaide and Christabel Mahan visited their brother Jesse in Honduras. Step-sisters Lois and Maggie also visited and worked for Jesse. Adelaide took this photograph of an unknown couple at the mouth of the El Porvenir River, the location of Jesse’s commissary.

Jesse took a business partner, a well-heeled, ambitious man named A. D. Baird. This man thought big. He decided that they needed a boat to transport the bananas to market, as there was too much spoilage getting them to the island of Roatan to be loaded on ships bound for the states and other ports. He had one built in Michigan, traveling there himself to supervise its fabrication. It was a forty-footer with two 100-horsepower gasoline engines.

When the boat was completed, Baird took it back to Honduras. He left Michigan, eventually taking the Mississippi River to New Orleans. Then he sailed east along the coast to Apalachicola, Florida, then across open Gulf waters to Key West. From there he proceeded to Cuba, where he hired a captain to make the journey across the Gulf to Honduras. Following a brief stop at Roatan, they arrived at the dock at the mouth of the El Porvenir River, which was the plantation headquarters. Baird’s big boat was finally home. How he had accomplished such an amazing feat is still a wonder to me.

When Baird got to the dock on his return, the first person he spotted was Jesse’s sister, Christabel, visiting from Brierfield. He fell in love at once and soon they returned to Brierfield where they had a grand wedding at her mother’s home on August 16, 1905. Anna even made Christabel’s wedding dress, which I now have.

Abraham Dubois Baird, Jesse’s well-heeled partner, far left, with amigos celebrating something. Note the fellows with musical instruments on the far right.

Father Alfora, left, a priest and Mexican refugee, posed with Baird in a studio photo. Baird made several trips to Mexico on business ventures and was returning home from there when he died in New Orleans.

Eventually, the Honduran government told Jesse that he would have to sell his banana business to the Vacarro Fruit Company or it would be nationalized. So he sold to Vacarro, which later became the United Fruit Company. Jesse’s partner, A. D. Baird, wanted new fields to conquer, so he and Christabel moved to Brierfield, where he intended to make a fortune as a dairy and mushroom farmer. He bought four hundred acres from my grandfather, Henry Cary Mahan, then went to Wisconsin to buy a herd of Holstein cows, which he had shipped by rail to Brierfield. He built a long milking barn with two concrete troughs, where the cows could be fed and milked at the same time, and he also constructed round concrete silage bins. He then built a home for himself and Christabel. Baird also rented several caves on the Cahaba River, where his visionary dream of raising mushrooms was to take place.

Baird’s dreams did not have happy endings. For a while he had luck with the dairy business. He milked twice daily, sending the morning milking by train to Birmingham while it was cooler. The afternoon milking, when the day was warmer, was shipped to Selma, a shorter trip. Unfortunately, the entire herd contracted hoof and mouth disease and had to be destroyed and burned. In addition, he never marketed a single mushroom. Thus ended his farming days. He and Christabel moved to the west end of Birmingham, where he started several business adventures. One was a business making steel-belted radial tires. According to family lore, he sold the design to Goodyear, but Goodyear never produced them because, presumably, they lasted too long; built-in obsolescence was the hallmark of ma

ny products of that day.

By this time, Baird was suffering from kidney failure, and he traveled to New York, where he could get the best medical treatment. There he had a kidney operation that was extremely rare in those days. Afterwards, he went to Mexico and then on to New Orleans, where he died on February 19, 1924. Christabel then moved to Dallas, Texas; her daughter Cornelia had earlier gone to Dallas, where she had a job teaching piano and working for the Catholic Diocese.

Jesse and Rosa stayed in Honduras after the sale of the banana plantation, living in the compound headquarters at the mouth of the river, from which he established cantinas in various locations on the mainland. Aunt Maggie Mahan, who also went to Honduras, told stories of how she would leave early on Monday morning on horseback to pick up the gold coins taken in at the cantinas, putting the money in her saddlebags and taking them back to Jesse. Jesse and Rosa had three sons—Jesse, Edward, and Gerald. Following Jesse’s death, they all came to the states, Edward because of his illness and Jesse to serve in the U.S. Navy. Jesse went on to make a career of the Navy, retiring in Norfolk, Virginia. Edward, because of his health, was not accepted in the military, but went to work in a shipyard near Los Angeles. In 1946 he moved from California to Brierfield, buying forty acres from Adelaide and building a house. The third son, Gerald, was disabled, walking with a limp. He kept getting in trouble, and finally A. D. Baird adopted him and brought him to Birmingham, but he could never control him, and he was returned to his mother.

Jesse Jr. also had a daughter who, like her mother, fell on difficult times when Jesse died. Rosa and the daughter became destitute, finally moving to New Orleans in the 1950s, where family gossip says the two became prostitutes. Rosa, it seemed to me, would have certainly been an old prostitute, but the story was widely accepted by the Alabama Mahans. On occasion, some Brierfield relative of Jesse’s would receive a pleading letter from Rosa, asking to borrow money. But during those post-war years, times were tough for the family and money for loans was not available.

Jesse and his second wife, Rosa St. Martin, on their wedding day in La Ceiba, Honduras.

I was always fascinated with Jesse’s Honduran adventure and dreamed of going there to visit his plantation to see if I could possibly find anyone who knew him, but most of all to find his grave. The first opportunity came in 1976, when my wife Linda and I began our plans. We wanted to start on Utila, and we contacted the Honduran Consulate in New Orleans for advice. They told us of a Mr. Rose on the island of Utila who might be able to help. Shortly afterwards, Linda and I flew to Mexico City and from there to the Honduras capital, Tegucigalpa. Then we went by land to La Ceiba on the northeast coast. From there we caught a primitive C-47 “Gooney Bird” to Utila. The weather was scalding, and the inside of the plane was as hot as a June bride in a feather bed. We sat on uncomfortable little metal seats near the floor. The plane flew only two or three hundred feet above the sea, and every once and a while we could feel the plane bobbing down and turning on its wing. I finally asked about it, and the pilot told me that he was delivering mail to the little bay islands.

Linda and I had never seen a place as primitive as Utila. There were no cars, and the streets were dirt. There was no hotel. But we did see one thing that stopped us in our tracks. When we passed the Methodist Church, our jaws dropped. It had the very same columns we have on our home at Montebrier, a house that Jesse’s father helped build in 1866. Jesse would have been quite familiar with the Montebrier columns, and we felt sure that he had designed those columns for the church. There were two other houses nearby in Utila with the same columns, and we supposed that Jesse might have built them as well. The columns—six inches square at the bottom up to four feet, then six-sided from there up to two feet from the top, then square again to the top—were common in our country, but the ones we saw on Utila were the only ones we saw in Honduras.

After we had walked around for a while, I asked someone where we could find Mr. Rose, and he pointed out the way, telling us that Mr. Rose rented rooms in his house. That was good to know, as we had no idea where we would lay our heads that night. We came to the house, which seemed pretty run down, its white and green paint quite faded. Backed up to the water, the house sat up on stilts like those I knew from the Gulf Coast. Linda decided to stand in the street in the hot sun behind the fence as I went on the porch and knocked at the door. Slowly emerging from the house was an ancient man on a homemade wooden walker. He professed to know nothing about a Jesse Mahan, and he also said that he did not rent rooms. I was rather worried that the whole trip was going to be for naught when I thought of a tape I had in my pocket. I had recorded Aunt Maggie telling a story about Old Bob, a celebrated criminal in Utila. I said, “Please, sir, can I play something for you?” and without waiting for an answer I switched it on.

Mr. Rose, seated on his porch at Utila, with his handmade walker—his chariot he called it—under his left hand.

The story went as follows: The year was 1905. Old Bob was a black man, well-known and liked in Utila, who with evil intent hid aboard a shuttle boat headed to the mainland for supplies. On board were ten or so passengers, including women and children. He shot all of the adults but one, who escaped, and threw the children overboard to their deaths. One was a baby that was found washed up on the Utilan shore. The survivor reported that the crime was the work of Old Bob, who was by that time was on the mainland. According to family lore, a posse led by Jesse Mahan went to the mainland to arrest him and bring him back to be tried in Utila. Once Old Bob was back, they made short order of the trial, and Bob was taken out and hanged from the highest ramon tree in the town. After he was buried, people became afraid that he hadn’t really died, so townspeople dug up the body to make sure. He was indeed quite dead, and he was quickly reinterred.

As he listened to the story, I could tell by Mr. Rose’s eyes that he knew it. When the tale ended, he got a wry look on his face and said, “I be damned if people haven’t been coming down here for years to ask me to tell them that story. You are the first son of a bitch to bring the story of Bob to me.” He looked out where Linda stood in the street. “That your wife?” he asked. I nodded. “Go get her,” he said. “I got somewhere for y’all to stay.”

He told us to sit down in the palmetto chairs, and he began to talk about Jesse. He even knew Maggie, and became quite animated telling us about how she once got in a fight with a local woman. That lady was still alive, he told us. Then he took us in to show us our quarters. Our room had shutters that closed, but no window panes or screens. The adjacent toilet was merely a hole in the floor, with the waste falling down into the water below. In the corner of the small room was a cold-water shower, which also drained into the water. Then he took us in to meet his wife, and she said she would cook for us. I had the first fried breadfruit I ever tasted, along with some local vegetables, all very good.

The next morning before we were to leave, Mr. Rose asked me if I had my machine, meaning my tape recorder. I handed it to him and he recorded a short message to Maggie about the settling of Utila by the British. Then he insisted on our meeting the woman Maggie had fought with. A dark-skinned woman, she turned out to be very nice. She said that they made up before Maggie went back to Alabama. She also insisted on cooking a breadfruit lunch for us.

Naturally, we were thrilled to meet these people who had known Jesse and the other Mahans, but we couldn’t stay any longer. We took the same hot plane back to the mainland that afternoon. Our next step was to find the Mahan plantation and, if we were lucky, Jesse’s grave.

We checked into a hotel in La Ceiba, which seemed luxurious after our night with Mr. Rose. Mr. Rose had given us the name and address of a ninety-year-old black man who had known Jesse Mahan, and I asked at the hotel desk for help in locating him. The desk clerk got us a chauffeur who drove for us the rest of our trip.

Our driver took us out to the site of the head of the railroad that ran twenty-six miles to the mouth of the E

l Porvenir River, where Jesse had his commissary and where the bananas were loaded onto boats to be taken to the ships. There we found an old man, who spoke no English but made me understand that he would guide us. The trip wouldn’t be easy, he said. He took us to a small open railroad car, the kind propelled by pumping a T-handle up and down. Linda and I took our seats in the front with the old man between us, and a younger black man, shirtless and powerfully built, standing at the T-handle. In the hundred-plus degrees he was profusely sweating, and his body odor bothered Linda and me. The old Honduran did not seem to notice at all. It was quite eerie skimming down that track—no sound but the pumping. Suddenly it dawned on me that we knew next to nothing about these two men, one of whom was armed with a machete. I found myself getting a little frightened, but my fright escalated when the car stopped and another sweating black man holding his own machete walked out of the bush. He began speaking in Spanish with the old man, and I wondered what was about to happen next. I realized then that the old man was asking him to help the other man pump the car. The young man put down his machete and stood next to the other. Together they began pumping us down the tracks. We went to the end of the line and back without incident.

We explored the area around La Porvenir for a while. I had brought with me a photograph of Adelaide and Aunt Maggie standing on the shore there, and the old man took me to the exact place the photo had been made. Linda and I had him take our picture there. We also located Jesse’s commissary and homesite. This was the headquarters compound of the Jesse Mahan and A. D. Baird banana plantation.

No Hill Too High for a Stepper

No Hill Too High for a Stepper