- Home

- Mike Mahan

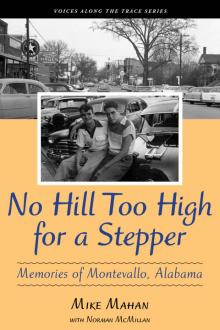

No Hill Too High for a Stepper Page 3

No Hill Too High for a Stepper Read online

Page 3

Mother and Dad kept White Leghorn chickens in a pen next to the coal shed in the backyard. There was a running debate in our neighborhood over whether our pale white eggs were as good as the brown ones laid by the Domineckers. I could tell no difference in taste myself, but once a year, when we dyed Easter eggs, I preferred our white eggs. It was a great ritual, and brought out our creative talents. Having boiled a dozen eggs the night before, I would get out five or six coffee cups, fill them almost full of water and add different colors of cake coloring. Then we would drop in the eggs, let them sit for a while, then lift them out with a strainer. Voila: those white Leghorn eggs had become Easter eggs. The neighborhood girls, Martha and Kacky Cox and Laura Ann Hicks, greatly outdid us boys, using wax pencils to draw patterns on the eggs before dying them. We boys settled for solid colors, though occasionally we would dye a two-toned egg.

I never think of Easter eggs without thinking of our dog Tag, a little short-legged mixed breed who found all the eggs we couldn’t, cracked them open, and slurped out the meat. I swear there was a smile on Tag’s face as he pranced around the yard after finding an egg, his tail turned up in a perfect semicircle.

There were five regular occupants in our house: Mother, Dad, Sister, Tootsie, and me. But Momma spent long periods with us, and in the summers my blind Aunt Lucille, who taught at the Talladega School for the Deaf and Blind, would come for extended visits. It became clear to me very early on that Dad and I were outnumbered. We were surrounded by strong, assertive women, and I began my life in a world that would be controlled by a series of petticoat dynasties. But I adored the women in my household and did not find their rule oppressive at all.

Tag was the best dog that ever lived. He tagged behind me wherever I went for over twelve years, and he was welcomed into the homes of all my Frog Holler and Shelby Street friends. Tag was buried in the back yard of our home on Shelby Street.

Many things occurred in my back yard including my sixth birthday party.

It was not to be denied that Mother was the dominant one in our household. She was a quite sincere, devoted Christian, and she tried to make her children follow suit. Every morning she conducted family devotionals taken from the Methodist publication, The Upper Room, but I didn’t cotton to it much. Plus, she made sure we got to Sunday School every week. A teacher in the youth department herself, she had a constant battle with me over preparing my Sunday School lesson every week. She did not want me to embarrass her by being unprepared when I went to Mrs. Kelly’s class. The truth was that I could not stand the lessons. I had liked Sunday School as long as we were coloring and drawing pictures, but when it came to memorizing Bible verses and studying the Sunday School lesson book, I quickly lost interest. On many occasions I conveniently “lost” my lesson book. But Mother would make sure I got another, and the battle over preparing my lessons would begin again.

When I was bad, it was Mother who outlined what punishment I would receive. A proponent of progressive education, she was not much for corporal punishment. Occasionally, though, she might cut a little switch from the privet hedge and half-heartedly go through the motions of switching me. But her usual choice of punishment was to make me sit in the bathroom with no form of entertainment. I found that very oppressive, until I discovered that I could keep a rope under the claw foot bathtub and use it for an escape out the window. All I had to do was tie the rope to one leg of the tub, step up onto the commode seat, and lift myself onto the lower window sash. From there it was an easy drop by rope to the yard.

I can’t deny that I was always a free spirit. I just didn’t have the constitutional makeup to stay where I was supposed to be. “Mike, I’m telling you, stay in the backyard or you’re going to be in trouble,” Mama would say to me, but in no time I was down at the creek or over at the Presbyterian churchyard. Anywhere but where I was supposed to be.

If my infraction was bad enough, then Mother would turn me over to Dad. “You are going to have to take Mike to the coalhouse, Red.” If she said “Red,” it wasn’t too bad, but if she said “Stanley,” then I could be assured it was “Katie bar the door” for me. She would say to Dad, “He sassed me three times this afternoon, Stanley, and after I explicitly told him he could not go down to the creek he went anyway.” It seemed to me that Dad looked rather forlorn as he motioned for me to follow him. It was like he too was being punished. As we approached the open doorway of the dirty coalhouse, he would remove his leather belt, and when we entered the dark, dusty room I would brace myself. The truth was that Dad never hit very hard, but still I would always dance the coal room shuffle as he administered the whipping. As the licks became weaker and weaker, he would warn me that I would get more where that came from if I didn’t mend my ways. “Do what your mother says,” he would always say. “She’s the boss.”

Mother, Dad, and me in the early spring about 1941. Mother had the kudzu vine behind us planted to block her view of the two-story Hartley house next door.

When I had been particularly bad, Dad would go in the house and come out to the coalhouse with his razor strop, which was four inches wide and thirty inches long. The strop was double, with a thin white leather one used for fine sharpening and a rough dark leather one used for the rougher work. It was the fine side that hit you, followed immediately by the popping of the rough piece. “Flap, clap,” it sang out. Dad assumed somehow that this was worse than the belt, but, though it made a great racket, it really hurt much less.

I remember feeling the true blaze of Dad’s anger only once, and that hurt me to the quick. This time he didn’t need to take off his belt. He wounded me with his words. I was about twelve and had gotten quite interested in mechanical things, spending a lot of time in the garage working on my bicycle. When I got tools from Dad’s toolbox, I was careful to put them back, but one day I figured out that it would be much better if his tools were arranged in a more orderly fashion. I found some old black paint and a brush and painted an outline for all of his tools on the wall, taking special pleasure when I drew in places for his prized box-end wrenches—all in graduated order. When I finished hammering in the nails the tools would hang on and putting the tools in their proper places, I stood back and proudly observed my handiwork. Dad was going to love this. I ran in the house and got Mother, who said she was extremely impressed with what a good job I had done. Then I sat on the porch awaiting Dad, who always worked an hour or two longer than Mother.

“Come see, come see,” I yelled as he approached the house. I motioned for him to follow me to the garage. I approached the workbench with great pride and a sense of accomplishment. “Ta da,” I said dramatically, motioning to the display of tools.

Dad did not smile. As he surveyed the tools, a sour look came over his face, and when he finally said something, he spoke through his teeth: “This is the biggest bunch of shit I’ve ever seen.”

I was crushed. I was heartbroken. I felt tears coming to my eyes. I watched as he yanked the tools from the wall and threw them back in the toolbox. “From now on, you can just leave my tools alone,” he said loudly. With those words, he stomped out of the garage, not waiting for a response.

That was probably just as well, as my hurt was fast turning to anger. Even if he didn’t like the job I had done, he didn’t have to act like a fool. I sat on the floor of the garage for a while and cried, and I couldn’t help thinking how much I hated that man. But if I have a virtue, it may be that I do not hold grudges. I just get on to something else. But for the moment I felt an intense resentment the likes of which I had never known.

I suppose Mother and Dad got along as well or better than most married couples. They were partners at work and partners at home. Whiskey was about the only thing I remember ever coming between them. Dad liked a drink, especially on Saturday nights. It would usually begin when Hoot Lucas drove up in front of the shop in his dump truck a little before closing time every Saturday. He was invariably the last customer of the day, g

etting a shave every week and a haircut every other week. At six foot two, Hoot cut an imposing figure. His black hair, which he liberally applied pink hair tonic to, glistened. His white shirt and dark overalls, bought across the street at Mr. Sam Klotzman’s store, were very clean and nicely pressed.

Hoot always wanted his black brogans with their brass eyes and shiny laces spit shined, and when I was there I would spend at least ten minutes on each shoe. When I finished, he would fish a nickel tip out of his pocket and hand it to me with a nod. The ten cents for the shine was added by Dad to the price of the shave, which was six bits.

Hoot always carried a paper sack which he would hand to Dad when he entered the shop. I learned quickly that it held a pint of clear liquid moonshine. When Dad finished shaving Hoot, he would pick up the paper sack and disappear through the swinging saloon doors of the beauty shop. I knew he would walk through Mother’s empty beauty shop and go into the back room where the toilet was. When he returned, I could always smell the moonshine. Afterwards, he and Hoot would joke around a little. Then, when Hoot drove off, we’d lock up the shop and walk home.

Mother could smell the moonshine too, and, as a teetotaler, she couldn’t help but complain. Sometimes he would ignore her, but more often Dad would get mad and leave the house, with Mother calling out behind him, “Go on and get loaded. See if I care.” But she did care.

The Man: Stanley M. Mahan Senior, my dad. There never was a hill too high for this stepper. Circa 1920.

Dad would sometimes go off with his drinking buddies—P. C. Wilson, Mr. Cunningham, Mr. DeSear, and Bloomer Wilson. Often they would go to Mr. Reggie Lawley’s house for a drink. Other times, since Dad had no car, someone would pick him up to go out to Randolph to buy more moonshine or illegal labeled whiskey from Burley Jackson. Burley had a garage where he worked on cars, but he also had a room in the back where he conducted his more lucrative business. There he kept pints of bootleg moonshine, and he would also sell you a shot of whiskey for two bits. Everybody drank from the same little glass, and no one ever knew of the glass being washed.

Where Dad went after he left Burley’s place was anyone’s guess. He liked to party and have a good time, and once he got that on his mind, there was no stopping him. I found myself quite sympathetic with Mother when she and Dad argued, because I had been taught at Sunday School that drinking whiskey was a sin and that it could break up a home. I certainly didn’t want it to break our family apart.

The real truth was that this wasn’t going to break up our home. I knew that intuitively. Dad would always come home, and as far as I could see there were no major repercussions. Mother would say how crazy it was that he would pay Burley Jackson two bits for a shot when that was all he got for a haircut. She thought it was a terrible use of his hard-earned money. But Dad paid little attention and sometimes walked out of the room singing, “Shave and a haircut, two bits, I’ve got a gal with two tits.” Mother would just shake her head.

I realize how much I am my parents’ son. Like my mother, in my profession of dentistry I often think of expenditures in terms of how many crowns or implants I will have to do to pay for the item. And, like Dad, I have a real attraction to a woman’s first measurement.

For whatever small failures Dad had, he was in so many ways a model father, looking out for his family and treating Mother with respect. He just had to adjust to the efforts to domesticate him, a man who had lived a free life until he was over thirty years old.

3

Momma and Aunt Lucille

It seemed to me that Momma set the tone for our family in many ways when she was with us. This short, chunky lady, her gray hair knotted on the back of her head, lived with us off and on for years, occupying the right bedroom in the back of the house. For a while I slept in the big double bed with her, and that always gave me a good, secure feeling. She never read me stories, but she told me about her early life in Carbon Hill and how her newly built home was destroyed in 1926 by a cyclone. Her husband, Samuel Hobert Wood, had run the commissary at the Carbon Hill mine and afterwards opened his own general store. But after the cyclone, he made the difficult decision to leave Carbon Hill and move to West End, in Birmingham, and start all over again. He opened a neighborhood grocery store that he operated until his death, which happened shortly before I was born. One of my regrets in life is that I never got to know this grandfather.

Though Momma never raised her voice and was always gracious, she wielded great power, the power of example. And she was always diplomatic, never siding with either Mother or Dad when they disagreed over something. Because Mother worked, the running of the house, when she was there, was left up to Momma, who had very high standards of housekeeping.

When I think of Momma, I always see the beautiful dining table she set. The main meal of the day, which we called dinner, was served around noon, and it was a formal affair. Even on weekdays, when the silver and fine china were not used, there was a starched white tablecloth and the table was formally laid. Momma thought the cloth had to be white, and I remember a bit of disagreement between her and Mother, who had bought a red tablecloth. She suggested that they use it one day at lunch, but Momma demurred, finally agreeing that it might be all right for breakfast or even supper, but never for the main meal of the day.

With Momma, my grandmother, the class act of my early life on Shelby Street.

On Sunday everything really had to be perfect. Emily Post herself would have been envious of the table Momma set. When we sat down to Sunday dinner, we always found linen napkins at each place as well as Momma’s fine sterling—a salad fork, a dinner fork, a spoon, and a knife. Also on the table was Mother’s fine white china with pink roses around the edges. Later, Tootsie thought Mother needed a better set of dishes, and she presented her with an eight-place setting of more modern design.

If we had soup, there would be a silver soup spoon. Everybody also had their own bread plate, with a little knife for spreading on butter, honey, or jelly. Butter, fresh-churned at Mr. J. K. Cunningham’s dairy, was on its crystal plate, and each person had his own salt dish. Sterling pickle forks were provided, and stemmed goblets for water and iced tea. China cups and saucers were also on the table, but I didn’t drink coffee because I was told that it would turn me black. To this day, I don’t drink coffee.

Daddy always sat at the head of the table, a stack of china plates before him. Before any food was served, he always said the grace. During the week, he always quickly said his standard blessing: “Father, make us thankful for this day and for this food we are about to partake. Bless it to our use and us to thy service.” But on Sunday he would ask a special blessing covering every sphere of our lives. This was a bit hard to take, far too long with all the fine smells giving rise to pangs of hunger. Once he had thanked God for everything, asked for forgiveness for all wrongs we did last week, and asked for guidance in the following one, he began to carve and serve the meat. With a routine that might have been choreographed by Sister’s dance teacher at Alabama College, he would pick up a large silver fork with a yellowed pearl handle and put a piece of meat on each plate. He handed the plate to the left, and it was passed all the way around the table to the person on his right. Then the bowls of vegetables were passed to the left, everyone serving himself.

The food itself was not particularly fancy, just basic home cooking—a pot roast surrounded by carrots, onions, and potatoes, clove-spiked pink hams, or a large platter piled high with golden fried chicken. If forced to make a choice, I would say that the fried chicken was my favorite. It resulted from a ritual that had begun the day before.

The killing and dressing of the Sunday chicken was an event both terrifying and exciting to me. Our maid, Maggie Hale, Momma, or sometimes Dad would wring the chicken’s neck, after which the bird would flop around on the ground in its death throes. Once still, it was put into boiling water and plucked of its feathers until the skin was white and clean. Then a sharp k

nife was stuck in its rear end and a large gash cut, from which the intestines and other organs were pulled. Only then could the chicken be cut up for frying. This process of cleaning the chicken, I was told, was called dressing the chicken, but I thought it was far more like undressing a chicken.

The liver and gizzard were saved to make gravy to serve over rice, mashed potatoes, or dressing. But I was far more interested in the pulley-bone, which everyone knew was my designated piece. At Sunday dinner, after I had cleaned the bone thoroughly, I would hold it up to one of my sisters, and we would make a wish and pull the bone apart. The one getting the small end was supposed to have his wish come true, though I never remember it working out that way.

After the main part of the meal was over, Momma and Mother cleared the table of all used dishes and then brought out dessert and poured coffee for the grownups. Sometimes Dad wanted his coffee with his meal, and the ladies would not object to this breach of proper etiquette.

Dad was addicted to his coffee. Every weekday he had a ritual before leaving for work. After finishing his eggs and bacon and grits, he took his coffee cup and saucer and put it on his plate, pouring some of the coffee into the saucer and raising the saucer to his lips and drinking it with a loud slurping sound. Then he would reach for any remaining biscuit and crumble it into the remaining coffee, picking up his spoon and eating the mixture with great relish. We called this “eating cuddly-muddly.” Unfortunately, I was never allowed to make cuddly-muddly, which is one way I think I might have learned to like coffee.

Food was most important to me, I guess, in the afternoon when I came home famished from school. I would immediately rush to the kitchen stove to find the leftovers from dinner. I didn’t mind one bit that the food was at room temperature. I would grab a baked sweet potato from the oven, break the top off and cover it in butter, then wolf it down. Candied sweet potatoes would go between two pieces of cornbread or in a cold biscuit, and sometimes I would put black-eyed peas or turnip greens and their pot liquors over cornbread. I never bothered to sit down to eat these feasts, just stood by the stove and ate off the oven top or counter by the sink. But usually I did sit down to cap off this culinary experience with a dessert—“nanner pudding,” rice pudding, or, my favorite, tapioca pudding. I think I liked the tapioca best because of the beady little eyes that stared out at you from the bowl. These afternoon feasts were superior even to Sunday dinners.

No Hill Too High for a Stepper

No Hill Too High for a Stepper